Euro zone yields without the ECB

ECB actions since 2012 artificially suppress yields of high-debt countries

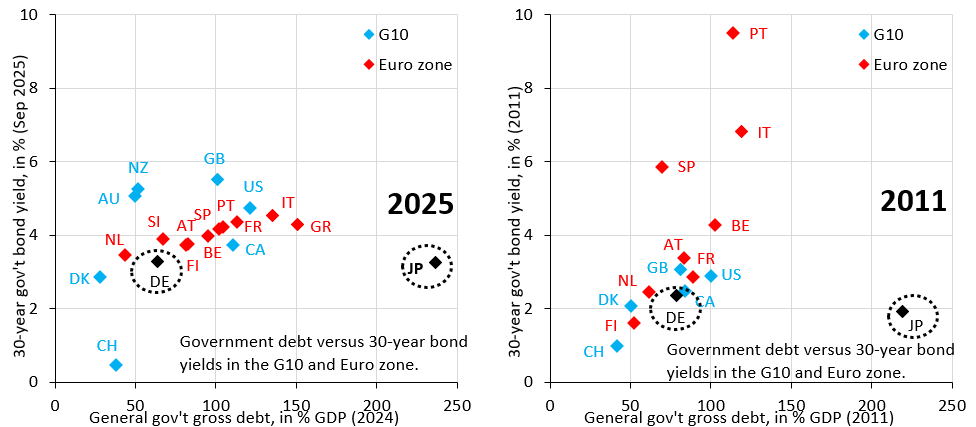

The million Dollar question in global finance is this: what would long-term sovereign bond yields be without over a decade of repeated quantitative easing (QE) programs? It’s impossible to know the counterfactual, of course, but there are clues. Two days ago, I wrote a post about how absurd it is that Germany and Japan have identical 30-year yields (around 3.3 percent). Germany’s gross government debt stands just above 60 percent, while Japan’s is now 240 percent. This suggests that the cumulative effect of Bank of Japan QE is massive and is suppressing what would otherwise be large risk premia associated with Japan’s high debt burden.

In today’s post, I look at the Euro zone. The ECB has done a long and growing list of things to suppress sovereign risk premia for high-debt countries. The list starts with Draghi’s famous “whatever it takes” comment in July 2012, which conflated survival of the Euro with avoidance of debt crises and defaults. It continues with Draghi-era QE, which began in January 2015 and ran for many years. Then comes Lagarde-era QE in March 2020, which departed from Draghi’s QE in an important respect: it dropped the capital key as a constraint on bond purchases, allowing the ECB to skew purchases to high debt countries if needed. Lastly, in July 2022 - at the peak of the COVID inflation shock - the ECB intervened heavily to cap yields for Italy and Spain and introduced its new anti-fragmentation tool - the transmission protection instrument (TPI) - which gives the ECB license to cap yields if it thinks they’re departing from fundamentals.

The cumulative impact of all this is no doubt massive and artificially suppresses long-term yields of high debt countries. But how to quantify the counterfactual of where yield would be without all this? The left chart above is the one I used two days ago to show how absurdly low Japan’s 30-year yield is. The right chart is exactly the same, only that it gives 30-year yields and debt levels in 2011, i.e. before Draghi’s “whatever it takes” speech. Debt levels for Italy (IT) and Spain (SP) were quite a bit lower, but their yields were substantially higher, a sign that markets were actively pricing sovereign risk premia. Yields for safe haven countries like Germany (DE) were lower, which points to an important - but often overlooked - flipside to yield caps for high-debt countries: yield caps reduce the safe haven appeal of low debt countries, because ECB removes the left tail from the distribution. The bottom line is that the cumulative effect of over a decade of ECB actions is to artificially push up German yields and hold down substantially Italian and Spanish yields.

Two closing comments. First, these ECB actions may feel good in the moment. I remember cheering on Goldman’s trading floor myself when Draghi said “whatever it takes” in 2012. But the long-term consequences of this kind of stuff are very harmful. After all, neither Italy nor Spain have ever done anything to bring down their debt overhangs. Instead, they - again and again - lean on the ECB for help, undermining its independence. Second, in both charts Japan’s yield is absurdly low, which might seem like an outlier, but Japan’s QE programs began well before 2011. Japanese yield suppression was already in full force by then.

All this has global ramifications. Artificially low yields in Japan and in the Euro zone are distorting global yields. That’s one reason why this year is seeing such pronounced upward pressure on long-term yields. Central banks are scaling back their presence in bond markets, which means that risk premia are reasserting themselves. The UK is at the leading edge of this. The Bank of England refuses to cap Gilt yields, forcing the government to make painful but necessary adjustments. One can only hope that the rest of the world follows this example.

UK adjustments are painful. But why are they necessary seeing all these other countries not making them?

And I would argue that all these ECB off-mamdate actions could be justified if they did help the euro area.

But in the end, all they did--and then some--was underwriting growth-harming fiscal and structural policies in the euro area. It is no accident that the region's growth performance has sharpy deteriorated for middle of the pack to abysmal since 2012.