How did we end up here?

Part 3: The US jobs machine is amazing, but only if you're in the labor force

Political polarization in the US is the worst it’s been in a long time and the labor market carries a lot of blame for that. In the years after the global financial crisis, lots of prime-age (25-54) men dropped out of the labor force and never rejoined, a trend that’s been especially acute among young men. It’s hardly surprising that - with this kind of thing going on - political polarization has risen.

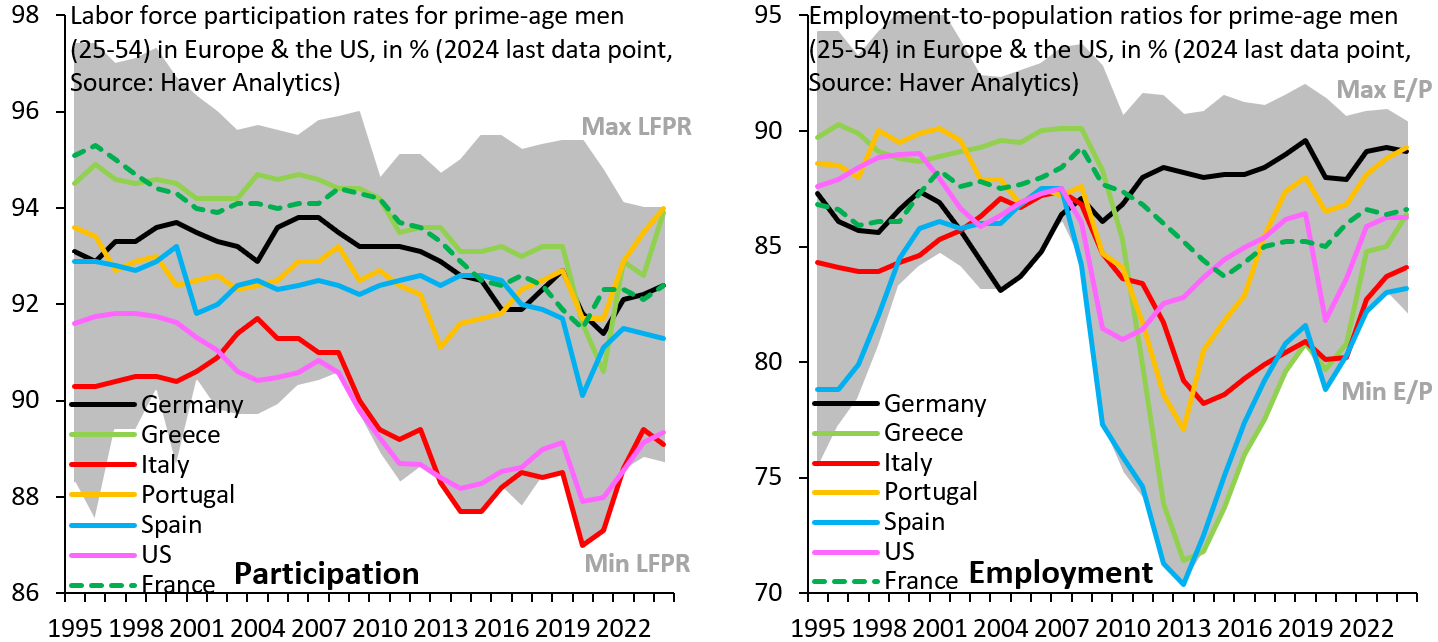

The fact that there’s a rising number of men on the sidelines jars with the perception of the US labor market as vibrant and dynamic. There’s actually no contradiction. The left chart shows labor force participation rates for men in prime working-age across key advanced economies. Participation in the US fell after 2008 and never rebounded, which makes the US something of an outlier versus other advanced countries.

The right chart shows prime-age employment-to-population ratios for the same set of countries. Even though participation in the US is low, employment of prime-age men compares favorably to other advanced economies, because - provided you’re in the labor force - the odds of getting a job in the US are high.

The fact that the American jobs machine is vibrant makes it all the more tragic that a rising number of men have been left on the sidelines. Indeed, all the talk of a tight labor market presupposes that it’s impossible to bring these men back into the labor force. If there’s one issue that deserves way more visibility, surely it has to be this.

This is an interesting combination. Two immediate reconciliations come to mind. First, that if there was a sudden shift of those who’ve dropped out of the program trying to find jobs, I’m assuming that they could not be absorbed seamlessly without also having impact on wages. Second, that assuming selection effects, many who are no longer searching lack the resumes or resourcefulness to get hired; they’re recognizing their own standing. Neither is rosy.