I’ve spent recent posts writing about the sharp rise in longer-term government bond yields, which is impacting the US as well as every other advanced economy globally. At the heart of this shock lies Japan, where the spike in long-term yields is far more dramatic than anywhere else. In today’s post, I’ll explain what’s going on and why Japan is much closer to a debt crisis than people think.

Japan’s gross government debt now stands at 240 percent of GDP. This exceptionally high level of debt is nothing new. Debt was 210 percent of GDP as far back as 2010. So why - if Japan managed to muddle along without crisis for over a decade - is its debt now a problem? There’s two reasons. First, debt levels have risen sharply all across the world since COVID, which is making markets much less accepting of out-of-control fiscal policy. After all, the UK and France have debt levels substantially below Japan, but are struggling with early-stage debt crises. Second, prior to COVID it seemed like inflation would always be low, which meant lower and flatter yield curves. That’s also gone out the window.

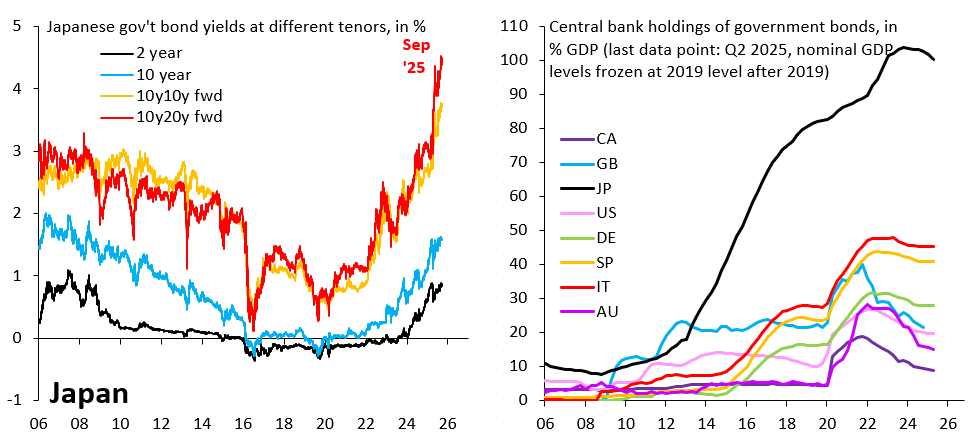

The left chart above shows what’s going on with Japan’s yield curve. It shows the 2-year yield (black line), the 10-year yield (blue line), the 10y10y forward yield (orange line) and the 10y20y forward yield (red line). The latter two are backed out from 10-, 20- and 30-year government bond yields and reflect what markets price for 10-year in 10 and 20 years’ time. What’s striking is how much the 10y20y forward yield has risen, which - as the right chart shows - is partly due to the Bank of Japan trying to extricate itself from its massive holdings of Japanese government debt. Indeed, given how little progress the Bank of Japan has made in this regard, the rise in 10y20y forward yield is quite shocking.

It’s tempting to think that the BoJ can just sit on its holdings, if its balance sheet run-off is causing yields to spike. But things aren’t that simple. The Yen has depreciated 25 percent against the Dollar in recent years, as global interest rates have risen. The Bank of Japan is under pressure to catch up to this rise in global yields, for fear that the Yen could go into another depreciation spiral.

The bottom line is that exceptionally high government debt is putting Japan in a terrible bind. If Japan sticks with low interest rates, it risks further Yen depreciation, which could cause inflation to run out of control. If it anchors the Yen by allowing yields to rise further, this could put Japan’s debt sustainability at risk. This catch-22 means a debt crisis is much closer than people think.

Of course, a debt crisis isn’t inevitable. It’s possible that the US goes into recession, which will cause US and global yields to fall. That will buy Japan time. But - in the end - the only sustainable way out of this catch-22 is for Japan to cut spending and/or raise taxes. For Japan’s population to accept that, Japanese yields may need to rise a lot further and/or the Yen may need to depreciate a lot more.

The BoJ is faced with a trilemma, with both fiscal dominance and financial dominance constraining its room to raise interest rates: https://open.substack.com/pub/thinicemacroeconomics/p/bank-of-japan-whack-a-mole?r=1oa8fn&utm_medium=ios

creo que la opción que va a utilizar es la que aumenten las tasas de interés ,la inflación nadie la quiere , el precio del petróleo es el que manda en este caso.