Lessons from 3 years of Russia sanctions

The West has the power to dismantle Russia with sanctions, it just doesn't want to

I’ve been working on Russia sanctions since the invasion in February 2022. What I’ve seen has shocked me. The bottom line is that the West is its own worst enemy. Recent decades were a period of maximum globalization, with lots of Western firms being formed that specialize in global shipment of goods, commodities and associated payments. Needless to say, these companies oppose sanctions - these are really just rules that prohibit certain international transactions - because they hurt short-term profitability. As a result, Western governments faced huge lobbying ex ante - before sanctions even went into effect - to water down their severity. Once sanctions went into effect, there was - ex post - huge sanctions circumvention. Western governments - especially in the EU - failed to stand up to this, partly because looming elections made them afraid to be more aggressive, but also in my opinion because of corruption. This post lists what I see as the key lessons from over three years of Russia sanctions.

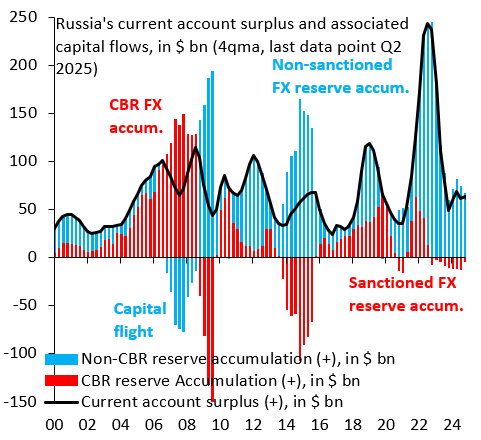

Financial sanctions don’t work on a country like Russia. When the US put financial sanctions on Turkey in 2018, it had a currency crisis and went into recession. Turkey is a current account deficit country, which means it’s constantly borrowing on global capital markets. Russia is the opposite. It’s a chronic current account surplus country, which means it lends to the rest of the world. This makes it much less vulnerable to financial sanctions. In practice, what did this look like? The West put sanctions on certain Russian banks, most prominently the central bank (CBR). But - since not all banks were sanctioned - this just meant that the recycling of Russia’s current account surplus migrated from the CBR (red bars in the chart below) to unsanctioned banks (blue bars in the chart below). Of course, there’s an easy way around this: sanction all banks. But this is equivalent to a full trade embargo, as Russia won’t export oil and gas if it can’t get paid. This highlights that - to hurt a current account surplus country like Russia - you need to hit the current account via exports rather than capital flows via financial sanctions. Financial sanctions have been a distraction.

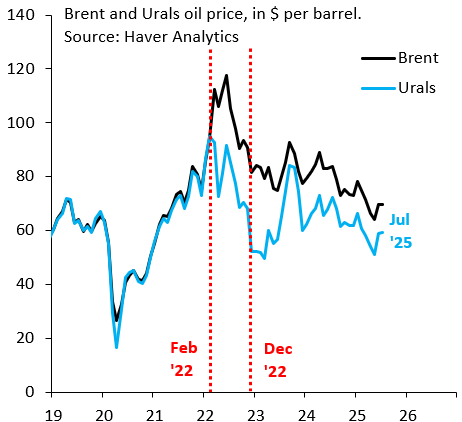

The G7 price cap is exactly the right tool to hit Russia. The cap targeted the current account, putting a ceiling on the price Russia gets for its oil exports. A cap of zero is equivalent to a full trade embargo, since Russia won’t export oil for free. A cap that’s equal to the market price does nothing. Anything within these two extremes deprives Russia of export revenues. The lower the cap, the harder Russia gets hit. This is where the ex ante lobbying I mention above comes in. Greek ship owners lobbied their government to set a high cap, so their business transporting Russian oil wouldn’t be impacted. The Greek government has a veto within the EU over key foreign policy decisions (which require unanimity) and so - when the G7 cap was introduced in December 2022 - the $60 level of the cap was essentially near the market price of Urals at the time (blue line in chart below). What should have been massively impactful was rendered completely ineffective due to Greek lobbying. Even worse, Greek ship owners then proceeded to sell Russia lots of their oldest oil tankers, helping it build its shadow fleet. This was ex post sanctions circumvention of the worst kind. The EU should have shut this down but it didn’t, again because of Greek lobbying.

Go early and go hard. Western governments slow-walked sanctions. The Biden administration is perhaps the best example. It only rolled out extensive sanctions on Russia’s shadow fleet of oil tankers after it had lost the election and no longer needed to worry about possible adverse effects on oil prices. This slow-walking has ended up being a huge mistake in hindsight. It would have been much better had the G7 cap been set low at the outset - say at $20 per barrel - in which case Russia would have gone into deep financial crisis because of the collapse in its current account surplus. That would have been the West’s best chance to end Russia’s invasion of Ukraine early. After all, it’s really hard to fight a war when your economy is imploding.

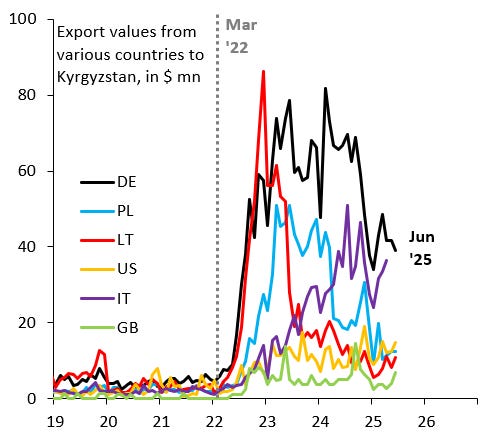

The EU is in a governance crisis. I talked about Western companies lobbying their governments in my opening paragraph. This problem is especially acute in the EU. I mention Greece and its ship owners above. German and Italian exporters, who ship goods to Russia via out-of-the-way places like Kyrgyzstan, are another example. The chart below shows monthly data for exports to Kyrgyzstan for a number of countries. The fact that the UK (green) and the US (orange) have been able to clamp down on these transshipments illustrates that this is simply about political will. In the EU, governments are able to look the other way, which is how we’re almost four years into the invasion of Ukraine and this appalling nonsense still goes on. I see - at the root of all this - an EU governance crisis, where the medium-term security interests of all the people in the 27 EU countries are playing second fiddle to the short-term profit goals of a few big companies and ship owners.

Is it still the case that the EU is importing Russian LNG and diamonds and the UK is sourcing diesel from Indian refineries of Russian crude?