The Politicization of Central Banks

Central bank bond purchase programs inevitably have political fallout

In yesterday’s post, I flagged how rising interest rates are increasing pressure on central banks to intervene in bond markets and cap yields. Such yield caps have inevitable political consequences, because they make high government debt levels look sustainable when in truth they are not. Like it or not, central bank bond market interventions shape the political discourse - keeping debt sustainability off the agenda - and can even sway elections.

In today’s follow-up post, I discuss the example of the ECB, which in July 2022 intervened heavily to cap Italy’s bond yields. At the time, Italian yields were rising, pushed up by the global inflation scare in the aftermath of COVID. That month’s surprise resignation of Mario Draghi as Italy’s prime minister risked making a bad situation worse. Georgia Meloni’s hard-right “Brothers of Italy” were poised to become the largest party in the ensuing elections. Markets feared this outcome. Risks were rising that a flight to safety - investors rotating out of Italian debt into German Bunds - could push Italian yields still higher, perhaps substantially so.

What should have happened at the time was for this to play out. A spike in Italian yields would have put debt sustainability firmly on the agenda into the September election and - perhaps - would have kept “Brothers of Italy” from winning. That didn’t happen because the ECB intervened.

It so happens that it was Mario Draghi who started the ECB down the path of quantitative easing (QE) in early 2015. Draghi’s brand of QE was constrained by the ECB’s capital key, meaning that government debt could only be bought in proportion to the size of each economy within the Euro zone. This constraint was critical, as it prevented the ECB from skewing bond purchases in favor of certain countries. In effect, this constraint ruled out abusing QE to cap yields of certain countries.

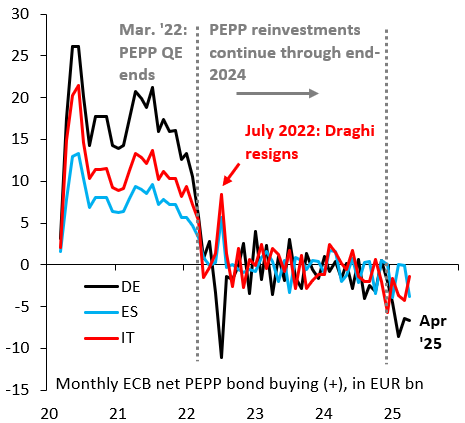

That constraint was dropped during the pandemic. The ECB began its pandemic QE program (called PEPP) in March 2020. The PEPP program continued through March 2022, whereafter it entered a hibernation phase: maturing bonds were reinvested to prevent ECB holdings from shrinking, which could have entailed rising bond yields, especially for high-debt sovereigns. In July 2022, something very unusual happened. As the chart shows, the ECB allowed large amounts of German Bunds to mature (black line). With the proceeds, it bought Italian (red) and Spanish government debt, effectively capping those yields at a critical time. This “skew” was only possible because the capital key had been dropped, giving the ECB more leeway in how it manages yields.

Three points are worth making. First, the ECB in July 2022 took Italy off the market, meaning its purchases of government debt (on the secondary market) were more than enough to cover the government’s net new debt issuance. In effect, this shielded Italy to a very substantial degree from the wrath of markets. Second, this may have helped “Brothers of Italy” win the election in September 2022. Without the ECB, Italian yields might well have spiked, steering the political debate towards fiscal conservatism and away from siren song of populism. Third, even though what happened in July 2022 is just one episode, the precedent has been set. Markets now price an ECB “put,” which is likely why Italy’s spread over Bunds is so narrow these days.

Central bank purchases of government debt are inherently political and therefore come with many adverse and perhaps unintended consequences. Those consequences are especially unwelcome in the Euro zone, where meaningful debt reduction in Italy remains elusive.

Incredibly interesting post. However, if I may, I’d like to make a clarification. What you describe does not happen in all jurisdictions. For example, the Eurosystem has recently introduced a new monetary policy tool, the Transmission Protection Instrument (TPI), designed precisely to reduce the confusion between monetary and fiscal policy. The TPI is activated only in the event of a malfunction in the government bond market (fragmentation, but not only that), considered “unwarranted”, meaning not due to fiscal irresponsibility on the part of governments. Pure and wise monetary doctrine. I do agree with you that this is not the case everywhere.

La amenaza de Meloni de la salida del Euro , se diluyó ?