No Erosion of US Reserve Currency Status

This week's IMF COFER data show no erosion in US Dollar reserve currency status

As my readers will know, I’m no fan of the ongoing debate over US reserve currency status for several reasons. First, most of the fall in the Dollar looks cyclical, given that it maps into interest differentials that price a more dovish Fed. Markets think tariffs will boomerang on the US. They’re really not thinking in any serious way about a loss of reserve currency status. Second, there’s the TINA (there is no alternative) problem. The Euro is the most obvious candidate to make inroads against the Dollar and it’s failed to do so in the almost three decades since its inception. The main reason for this is a lack of fiscal union and the moment for that - in my opinion - has passed. Third, reserve manager allocations are notoriously stable. Allocations to the Dollar didn’t rise in the many years in which markets celebrated US “exceptionalism.” It’s unrealistic to now expect a fall after only a few months, even with all the noise and uncertainty around tariffs.

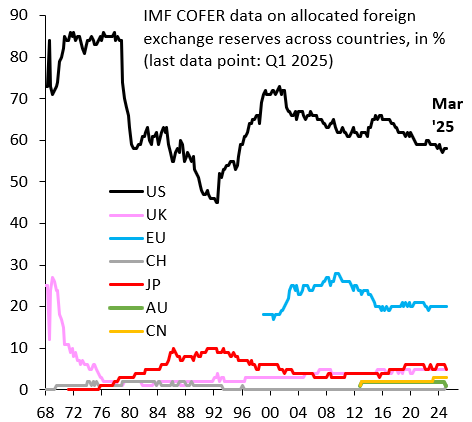

The IMF runs a quarterly survey on how official foreign exchange reserves are allocated and published the latest data (through end-March) this week. This cut-off predates the turbulence around “Liberation Day,” but it does capture the first big drop in the Dollar on the announcement of Canada and Mexico tariffs in early February. As the chart shows, reserve manager allocations to the Dollar were unchanged at 58 percent from December 2024 (black line) and - for that matter - from December 2023. The hurdle for reserve managers to shift out of the Dollar is high in other words.

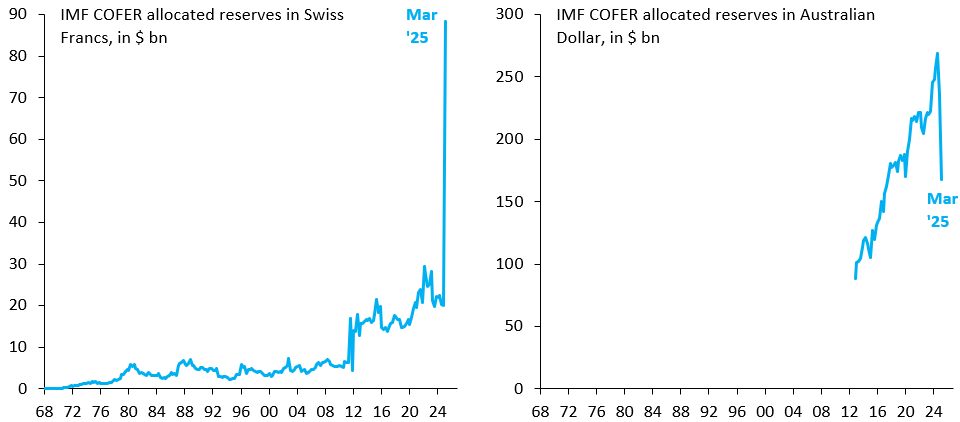

Beneath the surface, there was some weirdness in allocations to the Swiss Franc (left chart) and the Australian Dollar (right chart). But these shifts amount to very little in the big picture and may be revised away. The main takeaway from the latest COFER data is thus that the hurdle for the Dollar to lose its reserve currency status is very high. We’re not anywhere near that hurdle.

I might attach less importance to the high-frequency reserves manager data that Robin Brooks’ cites. The absence of a real Euro (Area) sovereign bond market and the limited convertibility of the CNY are no doubt handicaps for now, and I accept that.

But the dominance (now declining) of the USD in international reserves has only so much to do with the width and depth of the US Treasury market. It has a lot to do with the USD as the denominational currency for both debt and trade by private counterparties. The former is more important because a run on debt is the cause of financial crises. The growth of domestic currency debt markets, notably in the EM world, would mitigate those risks.

Trade (and trade finance) between third parties, on the other hand, use the US currency as a medium of exchange principally. They are short duration and self-extinguishing. The Euro could substitute for the USD quite easily.

We must also not forget of the games that the Fed plays to prevent de-dollarization of reserves, ostensibly in the name of financial stability. In actual fact, the use of USD swap lines are a gambit to deter foreign central banks from selling Treasuries to strengthen their currencies. The effect of these sales are as much higher UST yields as a weaker USD. Whether it is a Biden or Trump Administration, the Fed’s protective impulses remain the same.