The US Exorbitant Privilege

Trump's policy tumult does not appear to have damaged the US exorbitant privilege

In a recent post, I flagged that US reserve currency status emerged unscathed from all the policy tumult of 2025. IMF data show foreign reserve managers didn’t bail on the US, even after the chaotic rollout of reciprocal tariffs in the second quarter when the Dollar was tumbling. The lesson from that episode - at least for me - is that reserve currency status is much more deeply ingrained than many of us thought.

It’s one thing to avoid damaging US reserve currency status. After all, maybe there’s just lots of inertia to this kind of thing. But it’s another for the exorbitant privilege - the ability of the US to borrow at lower interest rates than its peers - to improve. Yet that’s exactly what happened last year. In today’s post, I’ll show my tracking of this and discuss why the numbers I show need to be taken with a large grain of salt. The US exorbitant privilege has a lot more cracks than a cursory look suggests.

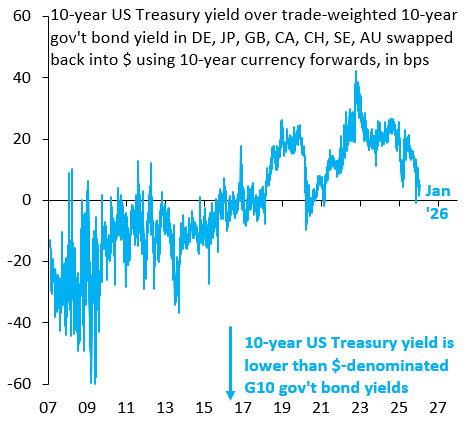

The chart above shows the premium of the 10-year US Treasury yield over the trade-weighted average for 10-year government bonds in Germany (DE), Japan (JP), Canada (CA), Switzerland (CH), Sweden (SE) and Australia (AU) after those yields are swapped back into Dollars using 10-year FX forwards. In the past, especially around the global financial crisis, the US enjoyed lower interest rates than its peers, which some link to greater liquidity and safety of US Treasuries. However, this “convenience yield” decayed over time, presumably as fiscal policy got more and more out of control. In the run-up to Trump 2.0, US interest rates were consistently above foreign ones, so the US was paying a risk premium. Counterintuitively, this premium faded in the course of 2025 and is currently near zero, the first time since COVID this has been the case.

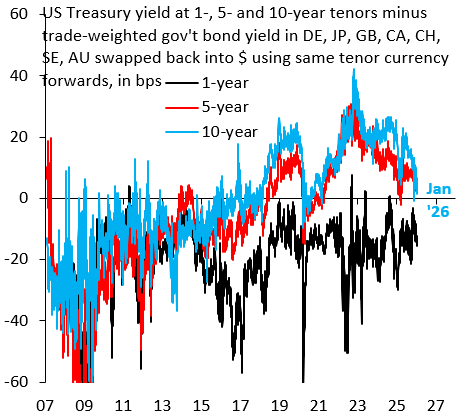

There’s two reasons why you want to take the first chart with a grain of salt. First, as I flagged in a recent post, Trump-related risk premia are forming at the very long end of the US yield curve. You can see that in the 10y10y forward yield, which means that my convenience yield, which is based on 10-year yield, misses this. In an ideal world, I’d calculate a 10y10y forward convenience yield, but FX forwards get pretty illiquid that far out, so this isn’t something I can do. The chart above does the next best thing. It shows how the difference between the US and trade-weighted foreign yield shifts up as the tenor of the convenience yield calculation lengthens. Going further out the yield curve makes the US exorbitant privilege look less secure. This issue might accelerate beyond the 10-year tenor.

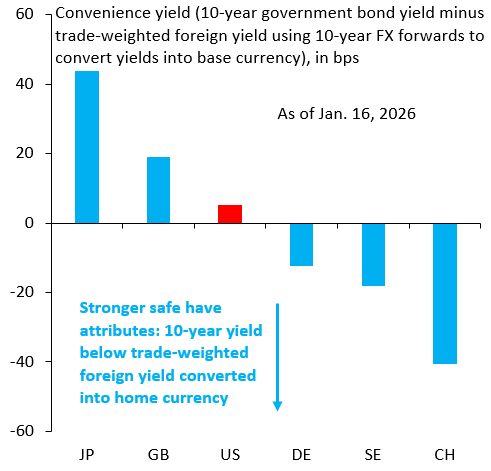

The second reason is that the US doesn’t actually look that great in a cross-country comparison. The chart above shows the 10-year convenience yield across countries, based on data from the end of last week. The US might be better than Japan or the UK, but it’s far behind Switzerland or Sweden, which markets are trading as the ultimate safe havens these days. The US exorbitant privilege has many blemishes.

Exactly where else is money looking for a safe haven to go? No matter how crazy Trump’s tariffs seem, compared to the economic suicide currently being practiced in the Euro zone, Japan’s debt problems, and China’s lack of transparency and reluctance to float the yuan, investing in the U.S. is an easy decision.

Excellent piece, Robin. You’ve captured the nuance of this "vanishing" risk premium perfectly—it’s rare to see someone map the trade-weighted 10Y basis against the fiscal narrative with this much clarity.

I kept thinking about Arvind’s [Krishnamurthy] framework while reading your section on the US exorbitant privilege. Given your focus on the resurgence of reserve demand despite the fiscal "cracks," his work on the safe-asset demand channel feels like the natural tether here. Even assuming his priors on the Treasury basis are baked into your tracking, it’s a powerful validation of the "convenience" wedge actually holding firm as a shock absorber while the long end of the curve starts to price in the policy tumult.

The way you’ve framed the premium fading to zero as a counterintuitive signal of reserve security—rather than just a cyclical fluke—is spot on. Really looking forward to the follow-up on the long-end risk premia