The US exorbitant privilege is failing

As fiscal policy runs out of control, Treasury yields are pushing above yields elsewhere

The exorbitant privilege is the US’ ability to issue lots of debt at low yields while also enjoying a strong Dollar. The exorbitant privilege looks like it’s in trouble. The Dollar has fallen sharply in recent months, while the 30-year Treasury yield is up to levels not seen since before the global financial crisis. Something is clearly off.

I’ve spent a lot of time trying to explain the fall in the Dollar and rise in longer-term Treasury yields. The fall in the Dollar looks cyclical, with markets pricing more rate cuts from the Fed than from other central banks in the G10. As US inflation continues to rise, pushed up by tariffs, I expect markets to give up on this view, which should help the Dollar rebound. The rise in long-term interest rates is more complex. Many countries did huge fiscal stimulus during COVID and failed to reign in deficits after the pandemic. The rise in longer-term Treasury yields is thus mostly about a global story, not a US-specific ones. But a US-specific thing is clearly also going on, which is what today’s post is about.

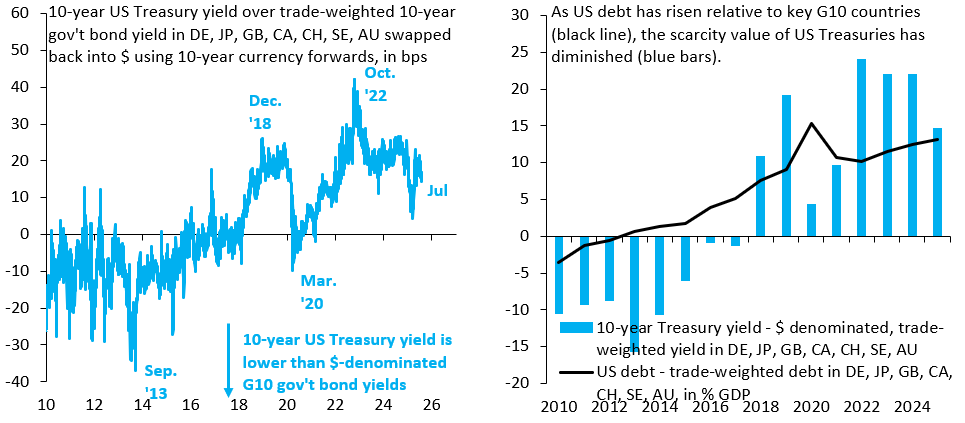

I calculate the differential of the 10-year US Treasury yield minus the trade-weighted average 10-year yield on government bonds in Germany (DE), Japan (JP), the UK (GB), Canada (CA), Switzerland (CH), Sweden (SE) and Australia (AU), where I use 10-year currency forwards to hedge the returns on these government bonds back into Dollars. This rate differential is therefore purely in Dollar terms and thus a good proxy for the “convenience yield,” i.e. whether global markets are willing to buy US debt at lower yields than debt from other countries because Treasuries are “special.”

The left chart shows a daily time series for this 10-year Dollar differential, starting in January 2010 and going through July 2025. It’s clear that the “convenience yield” on US government debt has disappeared. Where it used to be that the 10-year yield was on average around 10 bps below Dollar-denominated yields in the rest of the G10, there’s now a 20 bps premium. The exorbitant privilege looks like it’s gone.

It’s less obvious why the exorbitant privilege failed when it did and why the premium the US now pays hasn’t reacted to recent fiscal recklessness. The right chart tries to explore this. It compares the annual average of the time series in the left chart (blue bars) with a similar differential of debt-to-GDP ratios for the same set of countries (black line), i.e. for the US versus the seven other countries. The breakdown of the exorbitant privilege seems linked to the gradual rise in US debt relative to its peers.

Looking forward, if US fiscal policy continues to run out of control, this suggests that markets will demand a larger and larger premium on Treasury issuance. The US debt picture will become increasingly unsustainable.

me pregunto si las stablecoins será alquimia económica para estos males?

Could you elaborate how we could lose our exorbitant privilege (through excessive debt issuance) but still keep a strong dollar?

My initial impression is that eroding the desire for US debt treasuries and an increase in interest payments not in our control (whether we print $ or tax to get it) would make the dollar weaker, not stronger.