Why US tariffs are deflationary for China

US tariffs are a negative demand shock for China, which is left with no good options

China’s exports to the US have fallen sharply this year, while its exports to the rest of the world have soared in an almost one-for-one offset. It’s not hard to understand why exports to the US are down. After all, tariffs are pushing up prices for goods imported from China, as I discussed in a recent post. Higher prices mean lower demand, which means tariffs equate to a negative demand shock for China.

It’s less obvious why China’s exports to the rest of the world are up so much. There’s two possible explanations. The first is that China is using third countries to transship goods to the US. That would explain why exports to Vietnam and Thailand have risen so sharply. Both countries are well-known transshipment hubs. The second is that China is genuinely ramping up exports to new places. That’s likely also happening, because - in today’s just-in-time global supply chains - there’s limited warehousing capacity, so that goods quickly need to find a buyer once they’ve been produced.

Today’s post shows why either option is a deflationary shock for China. The first option - transshipment - should be obvious. Having to export via third countries adds to transportation costs, which cuts into margins and profitability of China’s exporters. The second option - exporting goods to new markets - is also a deflationary shock for China, because the price of exported goods needs to be lowered to generate demand.

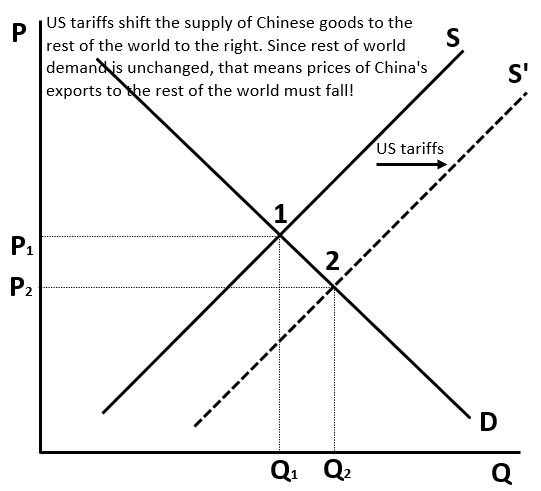

The simple chart above shows what’s going on. If China is redirecting goods that would have gone to the US to the rest of the world, this equates to a shift down and to the right of the supply curve. The rest of the world didn’t ask for this rise in supply, so China has to cut the price of its exports to generate demand. This is a move down the demand curve, which means falling prices, and could explain why exports to the rest of the world have risen.

In reality, what’s going on with the rise in China’s exports to the rest of the world is probably some combination of the two options. My point is that both are deflationary. In either case, the profitability of Chinese exporters is adversely hit. For a country like China, which is massively export-dependent and already teetering on deflation, that’s a worrying prospect.

Thanks for sharing. Wouldn't this imply part of the tariff is being paid for by the exporter, esp. in case of transhipment. Most argue that US import prices haven't gone down which means the tariff is completely being paid for by the US importer and maybe US consumer once it gets passed on. Curious to hear your take.

What if Rest of the World substitutes China in exports to the US, and then China exports to Rest of the World? This “implícit transhipment” would happen even if direct transhipment do not happen.